Memory and Modality through The Avalanches' Wildflower and "The Was"

- 8 mins

For many, music leaves some of the deepest impressions we have during our lifetime. One’s favorite song might often trigger a flashback, with a sudden return to those past moments they shared with the sound. These returns are accompanied with a flood of detailed sensory information that spread across our senses in what might be called an episodic memory. As we can appreciate in these moments, our memories are wrapped in complex, multi-modal associations that are encoded within our hippocampus, thalamus, amygdala, and various areas of our cortex. Thus, the act of recalling episodic memories stimulates these neural pathways just as they were activated when we first consolidated the memory. Björn Vickhoff explains the process wonderfully in his A Perspective Theory of Music Perception and Emotion,

“Even if the information is integrated in the hippocampus and the hippocampus is associated with long-term memory this does not mean that all memories are stored in the hippocampus. Rather the information is fed back to the perception and association areas. Episodic memorizing is to reactivate the perception process. This is what makes episodic memories so vivid. The process can be activated by any contextual cue. Since we live the event anew, this is by definition imagery. I believe that imagery and episodic memory is connected” (Vickhoff 2008).

Something as simple as the almost tangible link between the smell of freshly baked cookies and one’s grandmother is a product of the widely encoded information integrated upon each of our experiences, especially those experienced with strong emotion or personal meaning. Stefan Koelch describes this musicogenic meaning of musical “relations comprise memory representations… as well as associations with regard to an individual’s most personal inner experiences” (Koelch, 2011). I would like to explore this phenomenon through the lens of music cognition, focusing chiefly on how our modalities contribute to an experience of music that can transport us through memory and nostalgia.

The Avalanches’ Since I Left You is an album composed as a collage of thousands (~3500) of samples of records, movies, tv shows, and advertisements before it. This genre of music takes many names, but aligns within the traditions of plunderphonics. For The Avalanches, the absence of original musical material makes their record absolutely drenched in cue, reference, and signposts from the past. Their employment of appropriation, while frowned upon by musical history as a whole, allows their music to reach into the past and re-contextualize the samples they use within new frames of reference. While one could write an entire essay on these transformations alone, the effect of this method of production provides a massive launchpad from which we can dive into memory and nostalgia, both personal and cultural. However, the effect of this experience is, incredibly, a product of only our listening; how, then, would our experience change once we integrate a visual element such as that of an accompanying video?

For the release of their second album, Wildflower, The Avalanches collaborated with video artist Soda_Jerk to produce a music video well suited for plunderphonics. “The Was” is an audiovisual piece that mimics the stylistic composition of The Avalanches’ audio production in visual form. Set to a mix of songs from the album, “The Was” samples from films, music videos, TV and cartoons of the past in an effort to visualize the sonic collage of the past The Avalanches managed to build. The multi-sensory experience of enjoying “The Was” is a journey through the cultural iconography of the past and, as such, 1) directs the listener to marry the sound of _Wildflower* to the visual media of the past, 2) invites them to revisit memories of these audiovisual relics and the atmospheres of sentiment that are evoked, and 3) forms new meaningful associations between these samples and their personal memories, neurally and semantically.

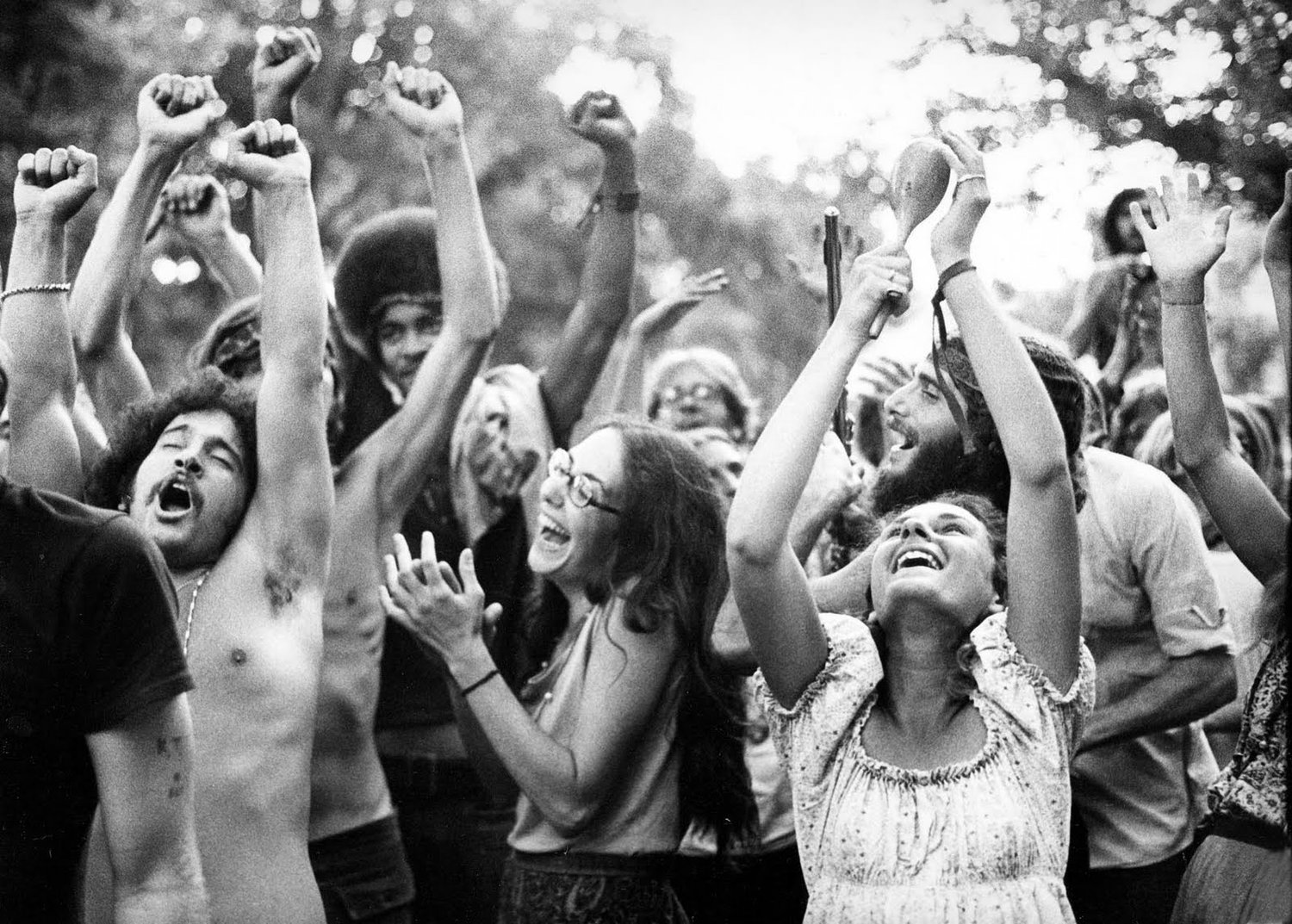

Like their past works, Wildflower uses found sound and sonic elements from unauthored music evoke a sense of nostalgia for a period across which their samples are spread. 16 years after the release of their seminal album, Since I Left You, The Avalanches made a return to the music scene with a new record, that continued their re-contextualization of sound that might be a little more in touch with today. While the album consists primarily of found and sampled sound, some tracks feature collaborations with contemporary artists that contribute new vocal or instrumental material. When one listens to Wildflower, they can hear the vintage quality of these samples, many of which have been lifted from wax. Mixing and mastering techniques and styles emblematic of their respective decade imbue these samples with their recording period, even as they have been chopped, processed, and reoriented within a new mix. Listening to “Sunshine” or “Harmony” one can hear vocal and string arrangements of the late 60’s, early 70’s with that characteristic lush quality diminished high end, reminding one of the easy-listening, blue-eyed soul period of the era. It might bring to mind the Summer of Love and a collection of artists (The Mamas and Papas, The Beach Boys, The Monkees etc.) that saturated the era.

All of these auditory cues may very well stimulate episodic memories, the phenomenon that Davies calls the “Darling, They’re Playing Our Tune” (DTPOT) theory of musical response (Davies, 1978). Something like Hal Blaine’s iconic drum intro into “Be My Baby” is immediately recognizable for many and likely there is a strong emotional response from those who are familiar of the song and the era. While direct reference to exact sonic material may not be recognizable for many within The Avalanches densely packed quilts of samples, it is the textural quality of this vintage sound, transposed through time, that is central to our experience of nostalgia. Admittedly, this task of sending listeners back into the past is might not be accessible for many without the musical history or associations. Thus, many musicians create video projects to supplement the artwork through a new sensory experience.

“The Was” splits Wildflower open and allows us to understand the work within a different modality that achieves a parallel effect, employing appropriation and composition to produce a video collage of cultural iconography. Film may be one of these mediums where we contextualize music and develop an understanding of what this past was emblematic of (even if it wasn’t experienced). SodaJerk deftly builds a visual story through the arrangement of 171 films, many of them situated as (cult) classics of counter culture in their respective era. Scenes from media of the past unfold like a travel log set to a mix of _Wildflower. In this way, the multi-sensory experience provides an even greater wealth of signs from which we may experience our memories from the past once more. But new now, is the experience of having these scattered audio and visual exchanges, dating as far back as half a century ago, enter into dialogue with one another. The conversation that exists when watching “The Was” connects the information we are receiving through both modalities, neurally and symbolically, the result spread across our memory systems. Considering the research suggesting that the consolidation and retrieval of memory is inherently bound within the cognitive structures like the hippocampus and cortex, one can imagine that their pre-existing memories recalled by the music and filmography of “The Was” are interwoven, encompassing now hundreds of audiovisual points of contact. After a viewing, the audience has been carried through time, visually, aurally, and perhaps emotionally and experientially, through memory.

Wildflower and “The Was” exemplify the power of re-contextualization as an apparatus of art making and the cognitive mechanisms able to form and reform rich personal memories. Experienced as a single modality, music provides more than enough sensory information (especially for musicians) that can drive us back to the moments and sentiments we’ve shared with the sound over our life. But once we add a secondary sensory experience, one as stimulating as video, we face a cross-modal event. Music videos and audiovisual projects alike arrange complex and disruptive encounters that seek to reorder and enhance the multimedia experience through our own involvement in the assimilation of audio/visual stimuli and sentimentality.

Works Cited

Davies, John Booth. The Psychology of Music. Stanford University Press, 1978.

Groussard, Mathilde, et al. “When Music and Long-Term Memory Interact: Effects of Musical Expertise on Functional and Structural Plasticity in the Hippocampus.” PLOS ONE, vol. 5, no. 10, Oct. 2010, p. e13225. PLoS Journals, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013225.

Koelsch, Stefan. “Toward a Neural Basis of Music Perception – A Review and Updated Model.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 2, 2011. Frontiers, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00110.

Koelsch, Stefan. “Towards a Neural Basis of Processing Musical Semantics.” Physics of Life Reviews, vol. 8, no. 2, June 2011, pp. 89–105. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.plrev.2011.04.004.

Since I Left You. Elektra / Wea, 2001.

Snyder, Bob. Music and Memory: An Introduction. MIT Press, 2001.

The Was (2016). YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3VN93T7m0-U. Accessed 4 Oct. 2019.

Vickhoff, Björn. A Perspective Theory of Music Perception and Emotion. 2008. gupea.ub.gu.se, https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/9604.

Wildflower. Astralwerks, 8 July 2016.