Soniweb: An Experiment in Web Traffic Sonification and Ambisonics

- 9 minsSonification of the Net

For the MCT’s sonification course, our group developed a system that collects and geo-locates web requests in real-time and sonified this incoming data. We were inspired by the paper and project Surfing in Sound which sonifies web-trackers via Ableton with an emphasis on user awareness and with potential of extending the experience into an audio-visual installation. A demo of their system can be viewed here. Another project with similar aims, Soundbeam, sonifies various trackers through SuperCollider while visiting a web-page as a lens into internet privacy. Our project, Soniweb, finds closer alignment with Surfing in Sound, employing a combination of Wireshark, Python, and Pure Data.

Our initial plan was to filter network traffic exclusively from the web browser and then analyze the HTTP response headers for information regarding the resources that are loaded when one visits a webpage. From there, we would send that data over OSC to Pure Data, a visual audio programming language and generate sound from it. However, we found (after extensive testing with various programs) that https webpages encrypt the view of the pages’ resources (the s stands for the SSL protocol) - this should have been more obvious at the beginning. This prevents a 3rd party application like Wireshark from spying in on the network activity and reading the data that is transferred. While this is a wonderful standard for the sake of security, it prevented us from going in that direction as Wireshark is unable to decrypt SSL layers. Another application, Fiddler, an alternative to Wireshark, is able to achieve this, however, its implementation has poor integration with Python and even less on macOS. So our vision broadened to include all possible network activity that is transmitted on a computer and we went with Wireshark as a tried and true stable of the data-sniffing community.

Implementation

We decided early on that it would be quite interesting if we were able to sonify the locations of the data packets that were being sent and received when one uses the computer. From a research oriented position, the sonification and spatialization of web data might provide the computer user with insights into:

- Where the data you see, while casually browsing the web or using a web-dependent application, actually originates from (digital-physical correspondence & global network monopolies)

- How one’s device is constantly sending and receiving information, even in a seemingly inactive state (the inextricable internet) and in contrast…

- How some webpages and applications take much more aggressive approaches in making contact with your device (web tracking & privacy overreach)

These guided our development and led us to tailor the data manipulation towards a sonified experience that could encompass these ideas. This led us to look for databases that would provide a massive list of IP’s with associated geodata (country, city and IP address). We ended up with one of Geoip2’s free databases, which appeared to be the most comprehensive, free collection of IP-to-coordinate entries available for this task. With their accompanying python package, we were able to import the database quite easily and look up the source and destination IP addresses of every packet that passed through our Wireshark server (tshark) that would be hosted in Python.

Half of us were first tasked with the development of the network sniffing script in Python. This involved working with a Wireshark wrapper for Python called pyshark which allows us to host a Wireshark instance and read and filter packet data completely within Python.

# Set up capture and filter by host IP and packet size

capture = pyshark.LiveCapture(interface="en0",

bpf_filter="host "+host_ip+

"&& length > 60")

This snippet of code constructed the capture stream and specified the network we were listening to (the Wi-Fi), which IP addresses we wanted to filter into our stream (our machine’s host IP), and what size we wanted the packets to be (this was to reduce the torrents of data that may be less relevant to our network activity).

There wasn’t too much documentation on pyshark’s full capabilities, so we spent a good portion of time getting familiar with the package as well as Wireshark, which the package relied upon. Once we had exhausted the aforementioned possibility of getting metadata from webpages, we began to program a simple packet to OSC script that would send OSC messages to Pure Data (Pd) when a packet was sent or received into the computer. We would have a Pd patch running simultaneously to the Python script to listen to our OSC messages with the port specified. Here’s the code that does this below

# Set up OSC server

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("--ip", default="127.0.0.1")

parser.add_argument("--port", type=int, default=8888)

args = parser.parse_args()

client = udp_client.SimpleUDPClient(args.ip, args.port)

Further development included generating longitude and latitude from the IP addresses and transforming them into ranges that we could eventually use in the Pd patch. We ended up splitting longitudinal values across 8 positions and 4 positions for latitude. This was a compromise due to the computational expense involved using 32 channels from which we would play multiple samples. Because we filtered in packets that either contained our host IP (the IP of the computer running the script) as the source IP or destination IP, we were able to send a single latitude and longitude pair along with a message giving the direction (sent or received). The protocol of the packet (TCP, UDP, TLS, DNS, other) and its length (or size) was also sent as OSC messages.

# Sent

if packet.ip.src == host_ip:

dst_resp = reader.city(packet.ip.dst)

client.send_message("/dest_name", dst_resp.country.name)

client.send_message("/direction", 0)

client.send_message("/ip_lat",

round((dst_resp.location.latitude+90)/60))

# 0 to 3 (4 degrees of differentiation)

client.send_message("/ip_long",

round((dst_resp.location.longitude+180)/51.43))

# 0 to 7 (8 degrees of differentiation)

print("Sent to "+str(dst_resp.country.name))

Sonification

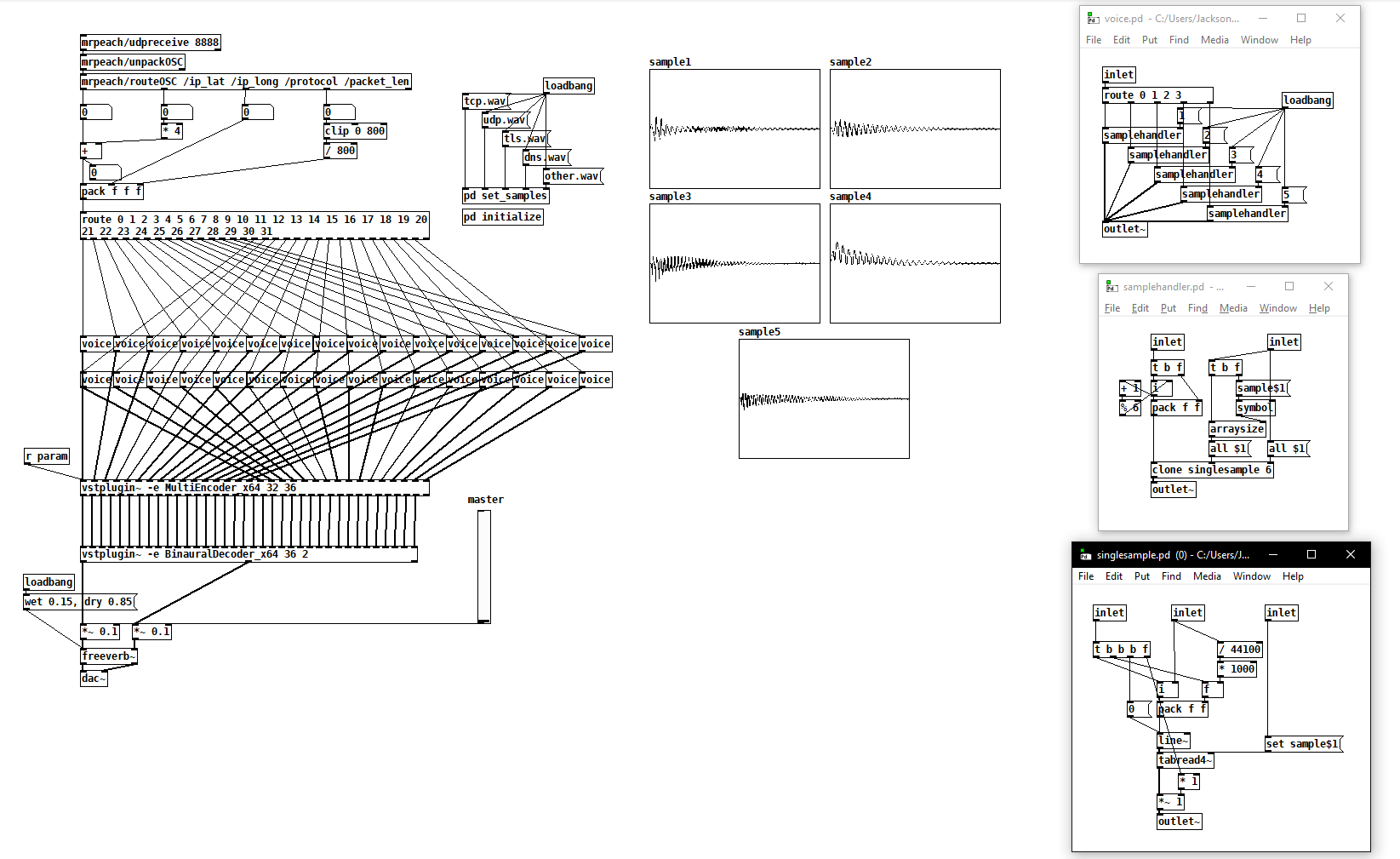

All the while, our third group member started development on the Pure Data patch simultaneous to our work in Python. He began with a sample handler that would play five different samples that corresponded to the protocol type, amplitude. We initially attempted ambisonics production through Reaper as a DAW but found a wonderful (and actively developed updated) library for Pd called vstplugin~ where we loaded the IEM plugin suite for ambisonics. The library worked quite well for our purposes and we were able to load each of our 32 channel’s azimuth and elevations as an initialization process. Each of the “voice” sub-patches contain five “samplehandler” sub-patches to play any of the potential five sounds given the protocol message. Within these sub-patches is one “singlesample” sub-patch that plays the sample with “tabread4~”. However, this sub-patch is cloned for times for the possibility of a single channel playing a particular sample up to four times simultaneously. This was built in due to the high frequency of packet data that we receive during the python script’s playback.

The Effect

When running the script and patch simultaneously, the network activity that your current machine is relaying is sonified and located in a 5th order ambisonics environment. The various bells ping around the listener as if they were sitting in the center of the Earth listening to the machines around them speak to one another. While we achieved our set goals, there are a few unanswered questions as to whether the packets that are being received are actually too quick to receive and process in real-time and may become backlogged over the course of a session. This may either have to do with limitations imposed by Pd, Python, Wireshark or the CPU power afforded by the user’s computer. In a recent update, converting one of the “if” statements to a dpf filter within pyshark’s instantiation made the incoming packets quite responsive to web browsing activity. However, it may be possible to mitigate these issues and enhance the sonification by generating the instruments within Pd rather than using sample files. This project has great potential for an extension into a live installation, one, perhaps, that asks the audience to connect their devices to a network hosted in the space so that they could listen to the network activity of their collective devices.

Works Cited

“Fiddler - Free Web Debugging Proxy - Telerik.” Telerik.com, https://www.telerik.com/fiddler. Accessed 19 Apr. 2020.

Hutchins, Charles, et al. Soundbeam: A Platform for Sonifying Web Tracking. 2014.

GeoIP2 Downloadable Databases « MaxMind Developer Site. https://dev.maxmind.com/geoip/geoip2/downloadable/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2020.

Green, Dor. KimiNewt/Pyshark. 2013. 2020. GitHub, https://github.com/KimiNewt/pyshark.

Lutz, Otto, et al. Surfing In Sound: Sonification of Hidden Web Tracking. 2019. ResearchGate, doi:10.21785/icad2019.071.

Pure Data — Pd Community Site. https://puredata.info/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2020.

REAPER — Audio Production Without Limits. https://www.reaper.fm/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2020.

Ressi, Christof. Spacechild1/Vstplugin. 2019. 2020. GitHub, https://github.com/Spacechild1/vstplugin.

Rudrich, Daniel. IEM Plug-in Suite. plugins.iem.at, https://plugins.iem.at/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2020.

Wireshark · Go Deep. https://www.wireshark.org/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2020.